Meet Dr. Postels

Dr. Douglas G. Postels, MD, is an associate professor of pediatric neurology at George Washington University and Children’s National Hospital. Dr. Postels has worked in global health since 2009 and has completed and ongoing patient-oriented research projects in western, eastern, and southern Africa. His main research site is the Queen Elizabeth Central Hospital in Blantyre, Malawi where Dr. Postels spends upwards of three months a year leading clinical trials in the Pediatric Research Ward and providing both general and pediatric neurological care to patients.

Following his medical education and training as a pediatric neurologist, Dr. Postels worked for a private group practice first in New Orleans, Louisiana and then in Albuquerque, New Mexico. Much of Dr. Postels’s patients at these practices were members of ethnic or racial minority groups, many of whom were Spanish-language speaking. To overcome any barriers to patient-provider communication, Dr. Postels taught himself Spanish.

During this time in private practice, Dr. Postels also volunteered in global health. With the Himalayan Health Exchange in Ladakh and Kashmir, union territories in the northern region of the Indian subcontinent, Dr. Postels lead international teams of medical students and physicians to operate mobile medical and dental clinics. In 2007, Dr. Postels travelled for a month to Blantyre to teach at the University of Malawi on a grant from the World Federation of Neurology, the first of many trips back and forth between the USA and Malawi. The following year, Dr. Postels returned to teach neurology to residents at the Queen Elizabeth Central Hospital on the International Visiting Professor Award from the Child Neurology Society. Dr. Postels also held teaching positions in Iran and in Ethiopia at the University of Addis Ababa where he continues to serve as a mentor and external examiner of students in neurology.

Dr. Postels recalls one young patient in particular from his early trips to Malawi as a visiting professor. After returning home from a full day of teaching, Dr. Postels got a message from the hospital. A nine-year-old girl had come in who had gradually lost the ability to walk, to feel, and to see. “I said, ‘give her a large dose of vitamins’ and that completely cured her problem,” Dr. Postels recalls. “That young girl was very impactful to me. It was such a simple fix for a problem that would otherwise have severely impacted her life.” This is where Dr. Postels sees the potential long-term impact of sustainable education and research.

Cerebral malaria is one such disease that has significantly different survival rates when care is accessible. Globally, untreated cerebral malaria is completely fatal. In the Pediatric Research Ward in Blantyre, Dr. Postels adds, “it’s reduced to 15%, the lowest in the world.” The recovery rates from disabilities resulting from cerebral malaria is equally astonishing. “The amazing thing about treating patients with malaria,” Dr. Postels reflects, “is the reversibility of the illness. We see patients going home blind, deaf, and separated from the world and they come back a few months later totally normal and it really is eye opening.”

Dr. Postels’s experiences in Malawi dramatically altered his future life. Witnessing the destitution of some regions of the world and absence of accessible medical care, in 2009 Dr. Postels decided to devote himself to leveling the global playing field. He sold his car and house, quit his job, and joined Medecins San Frontieres as a field volunteer. Stationed first in Lubutu, Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), Dr. Postels provided general medical care to both children and adults and helped to build capacity by training local providers. Following his time in Lubutu, Dr. Postels travelled to Port-au-Prince, Haiti, mere days after a devastating earthquake, where he lived without running water or electricity and assisted with the amputations of earthquake survivors.

After returning to work in the DRC, Dr. Postels was recruited to be a faculty member at Michigan State University. At MSU, Dr. Postels met Dr. Terrie Taylor and became involved in the Blantyre Malaria Project (BMP). Dr. Postels has since been focused on cerebral malaria, the most severe neurological complication of malarial infection that kills one in five children diagnosed. Those children who do survive often suffer from long-term neurocognitive impairments. Since 2010, Dr. Postels has worked with Dr. Taylor on BMP to study and treat pediatric cerebral malaria in Malawi in partnership with the University of Malawi College of Medicine and the Wellcome Fund, a global charitable foundation established by Sir Henry Wellcome. Dr. Postels also engaged his keen interest in teaching while at MSU and remains involved in several educational programs including a clinical tropical medicine course.

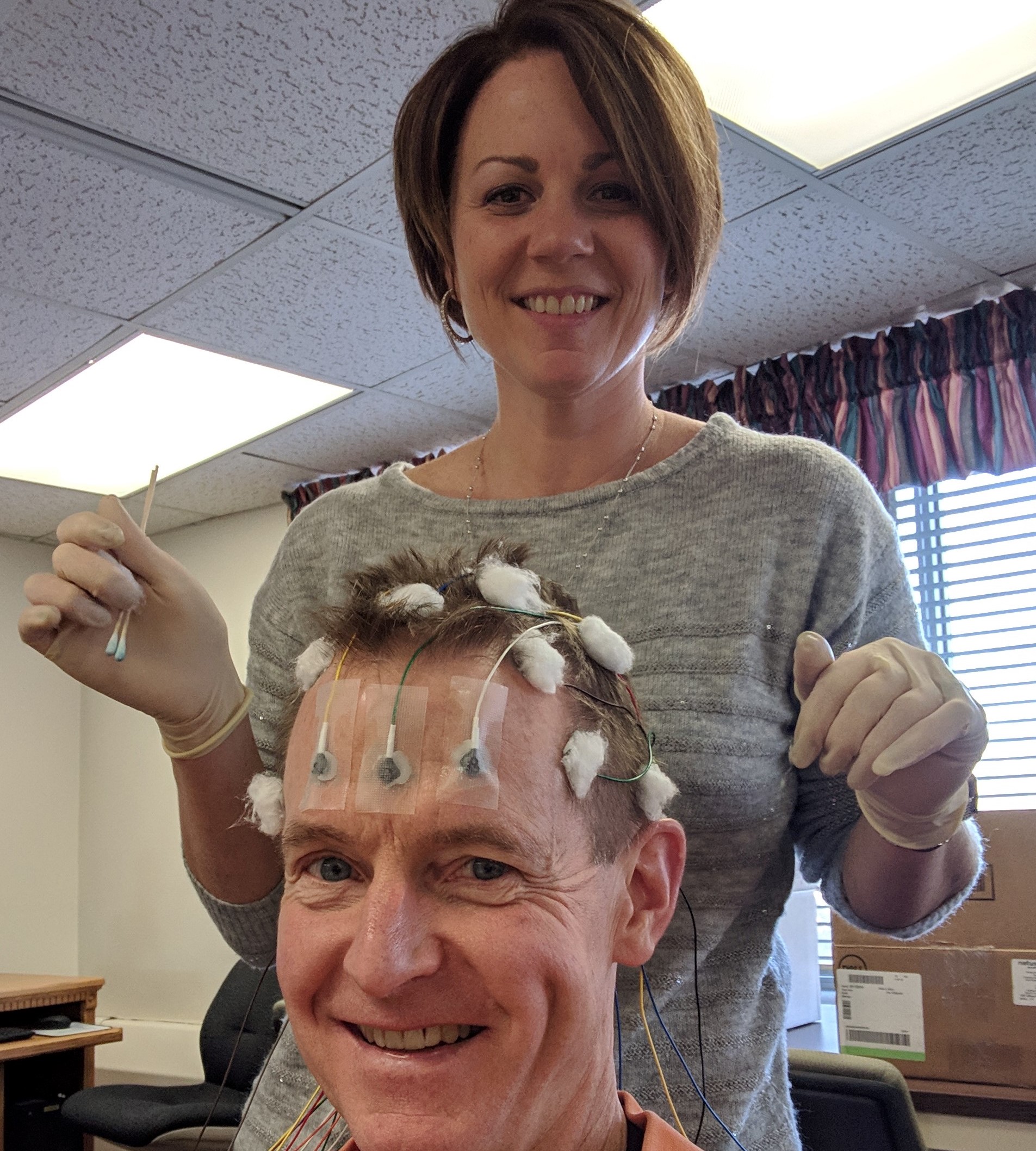

While at MSU, Dr. Postels participated in research on multiple NIH-funded grants to identify, understand, and evaluate possible interventions that would target factors leading to malarial infection and disease. When Dr. Postels started at Children’s National at the end of 2017, he was also about to begin as the co-investigator of an NIH-funded Phase III clinical trial, “Treating Brain Swelling in Pediatric Cerebral Malaria (TBS)” with his MSU collaborator Dr. Taylor. The randomized clinical trial focused on two interventions, intravenous hypertonic saline and mechanical ventilations, with the primary goal of decreasing rates of death and neurologic disability in children with cerebral malaria at high risk of death (read, Powerless). A main cause of death for children who develop cerebral malaria is respiratory arrest which results from cerebral swelling, cerebral herniation, and compression of the brainstem respiratory center. Mechanical ventilators help to preserve life, giving more time for the cerebral swelling to decrease. Intravenous hypertonic saline helps to get rid of extra water and could work to decrease brain swelling.

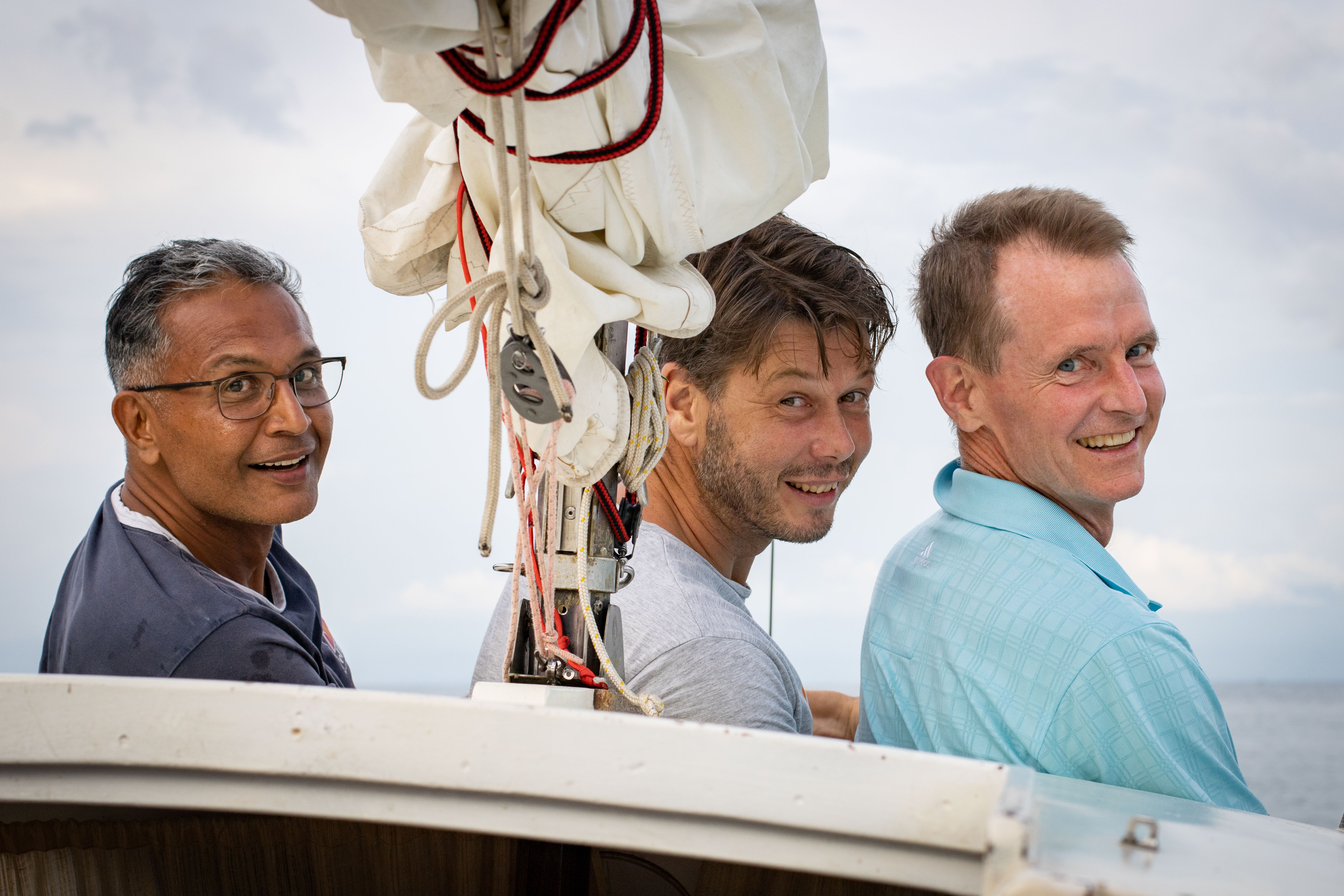

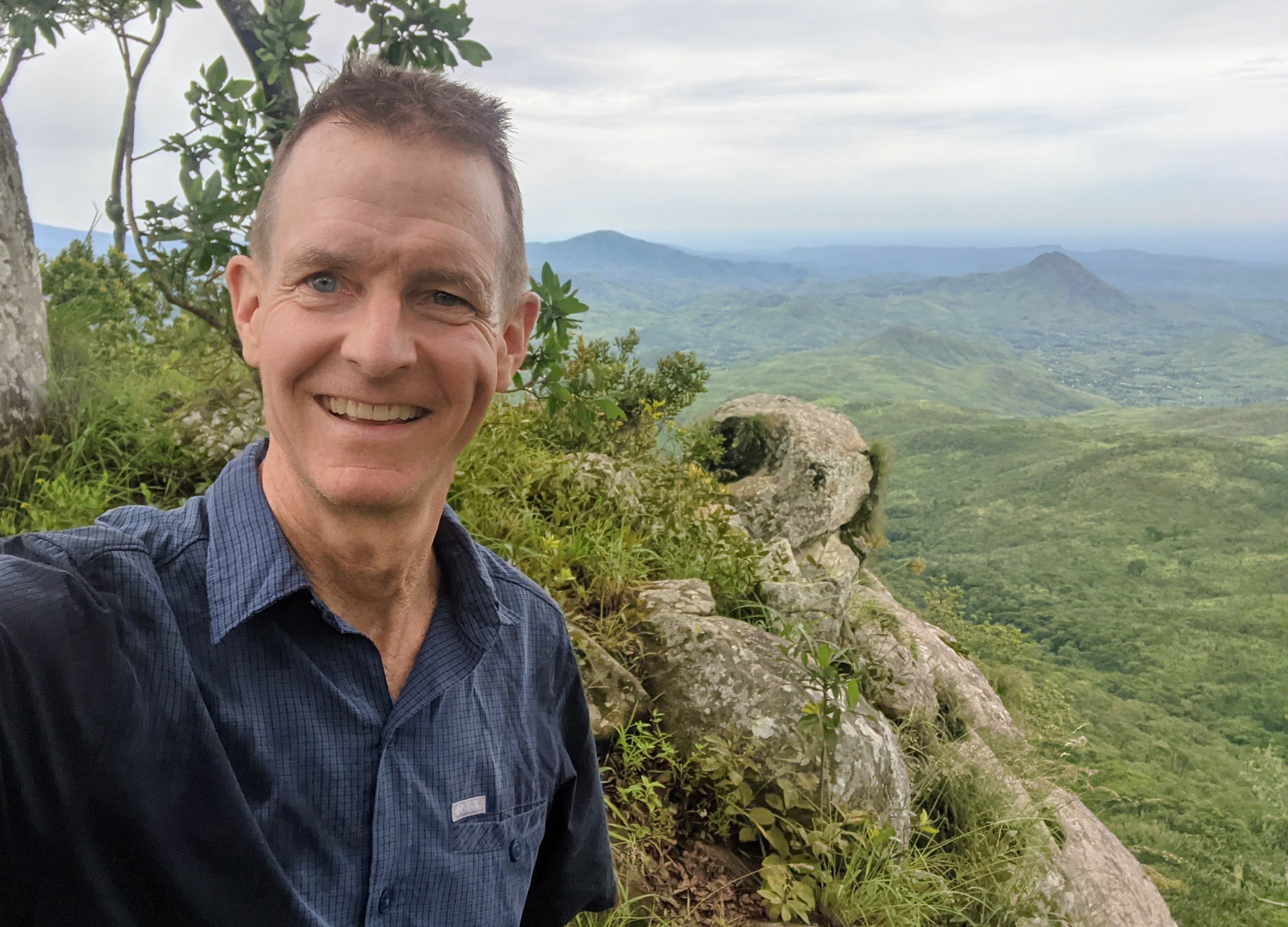

The Queen Elizabeth Central Hospital, where the study is based, is in an extremely low-resource environment. Malawi is the second poorest country on Earth, and the Pediatric Research Ward only admits children once they are already in a coma. In addition to providing the best clinical care possible, these patients are also enrolled in clinical studies to try and learn more about their illness and how it is affecting their body. Dr. Postels also works with the local team providing outpatient primary care to the surrounding community. Despite the difficulties of providing care without many of the resources Western patients are privileged to, Dr. Postels and his team in Malawi work very hard to ensure patients receive as close to the same standard of care as possible (read, The Board and Grateful). Dr. Postels considers Malawi an “ideal place to work” a “Lagniappe” thanks to “incredible” local collaborators and Malawi’s “gorgeous” physical terrain.

In addition to this clinical trial, two years ago, Dr. Postels was approached by a group of scientists at the NIH who were developing a drug to be used for cerebral malaria called DON. Dr. Postels wrote a medical protocol for its administration and applied for grant funding from the NIH. The funding was awarded with a start date of August 1st, 2021. This new project, a Phase I/II dose-escalation safety study of which Dr. Postels is the Principal Investigator (PI), is designed to assess the safety of the medication for use as an adjunctive treatment, meaning in addition to existing clinical standards of care. The clinical trial will begin enrolling patients in January of 2022.

In the meantime, Dr. Postels is very busy providing clinical care for his patients in the US at Children’s National and in Blantyre at the Queen Elizabeth Central Hospital and preparing to study a drug that could save thousands of lives every year from morbidity and mortality caused by cerebral malaria. At the end of the day, Dr. Postels’s passion for global health and international collaboration is about chipping away at global inequity. As citizens of a privileged environment in a first world country, he asks, “Why not do all that we can to level the playing field?”