Often, when health care workers arrive to work in sub-Saharan Africa, one of their first reactions is to the lack of medical tests and technology to which they are accustomed. Physicians sometimes think they need these to do their jobs. It’s a bit shocking to discover medical tests are simply not here. Neurology in the USA is heavily dependent on technology. As a neurologist I felt this acutely.

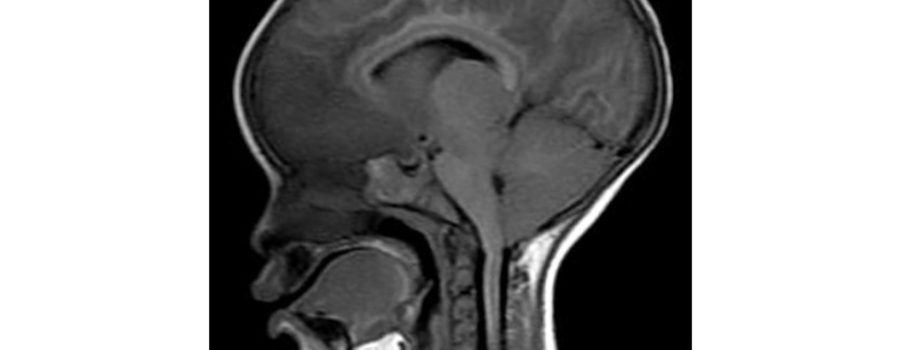

In the USA, we have it all technologically. For physicians and their patients, this means lots of testing and procedures, some of it reasonable, but much of questionable value in deciding on a diagnosis or treatment. Need a genetic test for a rare neurological syndrome? We can do that! And if, on the first go-round, the test comes back negative, we’ll squirt blood into a big machine and will sequence the patient’s entire genetic code, all 3 billion base pairs. In one day. Would looking at the brain’s anatomy be helpful? We can do an MRI for that. And if that isn’t enough, we’ll trace all the brain’s connections using diffusion tensor tractography. Or measure the brain’s blood flow using SPECT, MRA or CT angiography. The acronyms fly.

In Africa there is less, sometimes a lot less. In peripheral health centers, where most rural Africans received their medical care, the only laboratory test available is for malaria, and perhaps one for HIV. There is nothing else. No x-rays or ways to measure blood counts, electrolytes, blood sugar, kidney function, or liver function. Nothing.

To move forward, we need a bigger, stronger MRI scanner that can show us minute details of what is happening in our patient’s brains. And so far we have no way to get one.

In a district hospital, there are often more tests available if the radiology or laboratory equipment is not in disrepair, and if they have electricity and water. When moving up the African healthcare chain, such as in the hospital where I work, resources are more plentiful, but the comparison with the availability of testing in an American hospital is challenging to imagine. Queen Elizabeth Central Hospital, the location of the Pediatric Research Ward where I work, is the largest public hospital in Malawi, a country of 18.6 million people. To my knowledge, blood tests available in the hospital include ones for malaria, HIV, TB, a full blood count, kidney function, and an examination of spinal fluid. Cultures of blood and spinal fluid are available, too. The rest of it, doctor, is for you to figure out on your history and physical examination. We all hope that you are correct!

In truth, I don’t work in “Queen’s” itself. I work on the Pediatric Research Ward. Attached to the back of the hospital by a long corridor, lies the “PRW.” Children who are taking part in research studies are cared for in this 6 bed unit. Everything is clean and bright and there are lots of nurses to keep a careful eye on the patients. Several research projects enroll patients at the same time, but for most of the research we are doing the children must be in coma. Here, coma in children is usually from malaria, but it could be from meningitis, encephalitis or even something not infectious like a poison.

Compared to the rest of the hospital, the PRW has a lot of technology. There is a brainwave machine (EEG), an ultrasound to measure brain blood flow (transcranial doppler), and handheld testers for electrolytes, blood sugar, kidney function, and several others. We use these machines and blood testing to make sure the children are safe and to better understand their disease process. This technology has been very successful, and the Blantyre Malaria Project has made huge strides in the last 30 years, learning how to better care for critically ill children with cerebral malaria. The availability of these resources is wonderful until they are suddenly taken away.

Over a decade ago, General Electric donated an MRI machine to Queen Elizabeth Central Hospital. Michigan State University constructed a building to house it, trained staff to operate it, and have been intimately involved with keeping it going. In our work we used the MRI scanner a lot. The machine ran for years, rarely breaking down. But like all things electronic, its lifespan was finite and a year ago it scanned its last. My boss, Terrie Taylor, has tried several expensive and logistically challenging ways to resuscitate it, but so far things are not looking good.

This is a big problem. The MRI drove many of our group’s discoveries in the last decade. We use it to better understand the diseases we are investigating but also in clinical trials. In our current study, called “Treating Brain Swelling”, for example, we use the results of the MRI to decide which patients are eligible to receive our new therapies. And MRI is part of our upcoming clinical trial, called “DON”, which hasn’t yet begun.

An MRI machine is too expensive to put on a research grant application. It does not seem likely that the hospital can afford to purchase a new one. MRI manufacturers are not lining up to donate another machine.

What should we do? We need a functioning MRI to do our present and future work, finding new treatments to help children survive cerebral malaria. After months of trying to find the perfect solution, an alternative to a huge new MRI machine came to Dr. Taylor’s attention. It’s a portable machine manufactured by Hyperfine, a company in Guilford, Connecticut. The pictures it takes are not as detailed as what we have been used to in the past. We think the Hyperfine machine will let us squeak by for our current clinical trial, Treating Brain Swelling. But for the future clinical trials (like DON, which starts in a year) and for science and patient care to move forward, we need a bigger, stronger MRI scanner that can show us minute details of what is happening in our patient’s brains. And so far we have no way to get one.

And so, Big Wide World, does anyone know someone who knows someone with a spare 1.5 T or 3 T MRI scanner who wants to do some good for those quite a bit less fortunate than themselves? Hit ‘em up, please! We need it. Science needs it. And we would be eternally grateful.