I am upset.

A few days ago, a young child was admitted to the Pediatric Research Ward in coma. Her story was familiar. She was normal until she abruptly developed fever, had several seizures, and did not wake up afterwards. She was comatose when she came into the hospital. Unlike most Malawian children with fever and coma, though, she did not have malaria as the cause of her illness.

Here, cerebral malaria is much more common than non-malarial coma. Non-malarial causes can be due to infections or non-infectious. Viruses can infect the brain producing encephalitis. Bacteria may invade with meningitis as the result. Non-infectious causes include things like low blood sugar or toxins in environment.

The child had a fever, so it was logical that the underlying problem causing her seizures and coma was a brain infection. Her spinal tap was normal with very few white blood cells. This usually means a virus is the culprit. If we were in the USA, we would give her acyclovir until we could figure out the virus causing the problem. Acyclovir treats herpesviruses but isn’t effective against other viral causes. In the US it is all we have. In Malawi it is unavailable. So we took care of her the best we could and hoped her immune system would fight off the infection, restoring her to health.

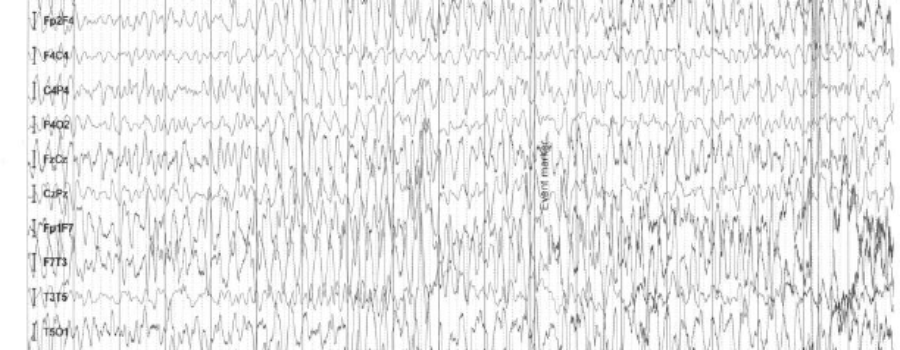

Over the next two days in the hospital, the child remained in coma. Her EEG (brainwave) on admission and each day afterwards showed several electrical seizures, without any physical signs. At times she would move into and out of electrical status epilepticus, where the abnormal electricity does not stop for a prolonged period. Status epilepticus (“status” for short) is a medical emergency. The longer it goes on, the more difficult it is to stop. Once status is identified, either by physical seizures or on EEG, if it does not stop by itself, physicians give several anti-seizure medicines in sequence as treatment. We wait a few minutes between each drug to allow penetration into the brain, hoping the abnormal electricity will cease.

By this time the EEG was beginning to flatten, due to all the anti-seizure medications I had given her, but the seizures would not stop

Immediately after morning patient rounds, the young child was having EEG electrodes applied for her morning study when she abruptly stopped breathing. Four of us were present and went to work. One held a mask against her small face, the second squeezed a bag to push air into her lungs, the third put a tube down into her stomach to evacuate the air that was accumulating as the patient was “bagged.” And I was in charge, watching her EEG and ordering the anti-seizure medications to stop her electrical status epilepticus.

In the USA, we start treating status epilepticus with lorazepam, a medication like Valium but shorter acting. If that doesn’t stop the seizures, we escalate to phosphenytoin, a safer version of the drug phenytoin (Dilantin). If the brain doesn’t quiet with that, we move to phenobarbital. Phenobarbital is a potent anti-seizure medication, but it depresses the drive to breathe. By this time, due to both the seizures and the side effects of the medications, American children are moved into an intensive care unit, if they are not there already. If the child with status epilepticus’ breathing isn’t already abnormal, it will be after we add phenobarbital or more medications if that does not stop the abnormal electricity.

Here in the Pediatric Research Ward, the only other drug available that might work in this situation is ketamine. Our patient’s seizures were ongoing. She still wasn’t breathing on her own. The bagging continued. I gave her a large dose of ketamine over 10 minutes and started a continuous intravenous drip. No luck. The abnormal brain electricity continued. I gave her more phenobarbital and more ketamine. No luck. I repeated them both again. By this time the EEG was beginning to flatten, due to all the anti-seizure medications I had given her, but the seizures would not stop.

I was stuck. If I gave her more phenobarbital or ketamine (which was all I had available) I would flatten her EEG and stop all electrical activity in her brain. It would take at least 72 hours for the medicines to wear off and we could not “bag” her for 3 or more days. We had no available mechanical ventilator and she would die. And if I did not give her more medications, she wouldn’t breathe because of the ongoing status epilepticus. She would not breathe due to her underlying illness and she would die.

I was helpless as I watched this child die in front of me.

As a physician, you partially steel yourself against these things. That evening, though, my roommates asked me why I was so quiet. I thought about this young girl, her mother taking her back to her body home village wrapped only in a sheet, her life cut short and me powerless to stop it.