Though caring for patients in the USA and Malawi is vaguely similar, improvisation to make up for a lack of resources is a consistent theme in Africa. One interesting difference between them is the contrast between the way that members of a medical team communicate with one another. The workflow in American and African hospitals is very different, but over the decades, Terrie Taylor, the head of the Blantyre Malaria Project has created a well-oiled patient care machine.

In the USA, we use EMRs (electronic medical records) for health care communication. Most American physicians agree that they are awful. In my patient care life, I spend as much time typing as speaking with families and examining their children. Even more absurd is that EMR systems can’t communicate with one another. I’ve had to learn 6 EMR systems in the last 10 years and they are all unique. If a doctor’s office uses one system and a hospital another, electronic communication between the two is impossible. If a primary care doctor wants to learn what happened to their patient while hospitalized and the two systems are not the same, the hospital must print out the hospital record to be hand carried or mailed to the doctor. This is absurd. Without a requirement that different EMR systems be able to communicate with one another, the efficiencies and patient safety that EMR systems were supposed to bring us are a huge failure.

With one exception.

Within a single doctor’s practice or within a hospital, electronic communication is great. Doctors order medications by computer. The pharmacy receives the order instantly, fills it, and sends the medication to the patient’s nurse. Physical therapists can be summoned to a patient’s bedside with a few clicks. Nurses need not remember when or to whom they should give medications, as the computer tells them to give Medicine A to Patient B in Room C at 8:27 a.m. Compared to when hospitals used paper for physician orders (remember pneumatic tubes?), electronic communication within a hospital has created efficiencies that allow extremely complex medical care to be provided on time.

Queen Elizabeth Central Hospital, where I work in Malawi, has no discernable electronic system for anything. If a doctor writes an order for a medication, a nurse must walk to the pharmacy with a page from the patient’s chart to collect the medication. If the patient needs physical therapy or an x-ray, obtaining it requires a piece of paper being hand delivered, a phone call, or both.

The children hospitalized on the Pediatric Research Ward are very medically complex and require much more timely care than is usually provided to patients cared for elsewhere in the hospital. Over the years, systems have been developed to care for these children, most of whom are on the edge of death when admitted. When a child is identified somewhere in the hospital (the general pediatric ward, the emergency department) who might be a candidate for one of our ongoing research studies, a group WhatsApp text goes out to 31 people. When the child physically arrives to the Research Ward Admissions area, the team springs into action. The child is first stabilized medically and given oxygen if needed. The patient is simultaneously evaluated by a nurse, physician, and a clinical officer, analogous to a physician’s assistant. After receiving the results of screening blood studies, a second nurse takes the family aside and requests consent for the child to be admitted to the Research Ward into one or more research projects. After consent is signed, within a few minutes the team has obtained a history, performed a physical examination, put in an intravenous line, drawn blood, done a spinal tap, obtained an EEG (brainwave) exam, an ophthalmological exam, ultrasounds of the brain and vital organs, and sometimes a brain MRI. To watch it is to appreciate the beauty of an efficient group dance.

The children of Malawi, just like those in the USA, deserve the best we can provide.

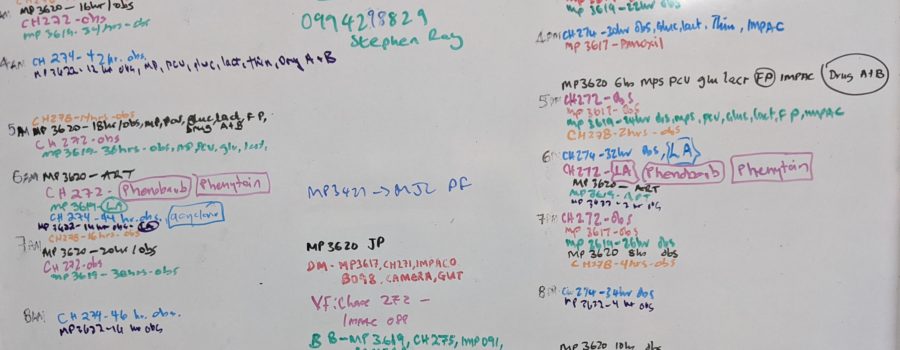

Once the critically ill child is physically moved into the Research Ward itself, they must have their vital signs (temperature, pulse, respirations, etc.) taken every two hours. Many of the patients are on several medicines (antimalarials, antibiotics, antiseizure medications), all of which are given at different times. Keeping this all straight for these critically children is challenging, as each patient’s requirements are unique. There is no electronic system that alerts a nurse to give a medication or change intravenous fluids at a specific time. To keep it all manageable, we don’t use an EMR. We use a white dry erase board.

The Board is a colorful work of art. The 24 hours in each day are listed in two columns. Next to each hour is an entry for each child, designated by color and identification number, indicating the laboratory study, medicine, or other treatment to be performed during that hour. In each child’s paper chart is a checklist that corresponds to the items and times on The Board. Each hour, a nurse looks at the white board, notes the tasks s/he needs to perform during that time interval, and checks them off in the patient’s chart after they are completed. When we are busy, like now, The Board is beautiful.

Though we may not have the efficiency of an electronic system like we do in Washington DC, these systems work extremely well. Even in a low resource environment like Malawi, complex, timely, and high quality medical care is possible. And why not? The children of Malawi, just like those in the USA, deserve the best we can provide.