A few weeks ago, a physician colleague at Children’s National Hospital in Washington DC contacted me. Almost simultaneously I received an email, text message, and phone call. This is highly unusual. I’m not an expert in much except diseases of African children. What could they possibly want?

A 5 year old boy was at the hospital and his doctors thought I might help with his medical management. The child was well until 2 days before coming to medical attention with fevers and body aches. His mother took him to his pediatrician for evaluation. Their primary care physician, knowing the family, asked for a travel history. “Has he been outside of the United States recently?” “Yes.” He had been staying with relatives in Nigeria for the last few weeks and returned home to Washington DC less than a week ago. His parents had immigrated to the United States a few months before he was born. This was the second time he had traveled to his ancestral homeland. The family had not consulted physicians before traveling. None of them had received recommended pre-departure vaccines nor were they taking malaria prophylaxis. The boy’s pediatrician recognized that, even though the child did not appear very ill at this time, he could rapidly deteriorate. She referred the boy to our hospital for a blood test for malaria. It was positive.

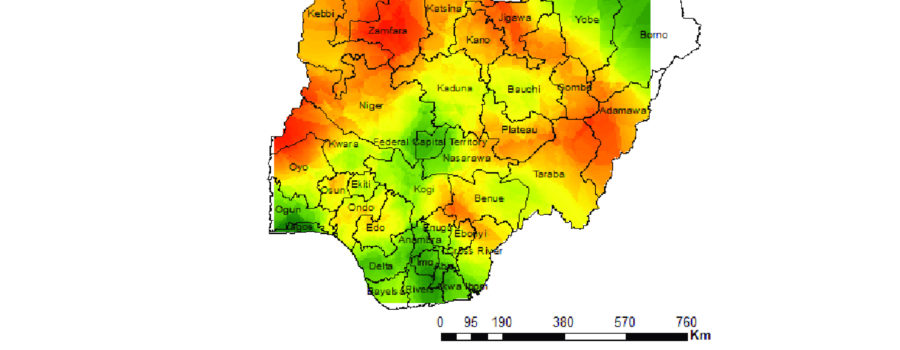

Annually, there are about 1500 cases of malaria diagnosed in the United States. Seventy percent of cases are in travelers returning from Africa. West Africa has the greatest burden.Nigeria is the epicenter. The large majority are in travelers classified as VFR, Visiting Friends and Relatives.

Now that they had the knowledge that they were newly at risk of dying from malaria, they needed to take action to stop themselves from joining the list of grim statistics, tragically dying from this preventable illness.

When people live in areas where malaria is transmitted, they may frequently be bitten by malaria-transmitting mosquitoes. The first few times this happens they become ill. They take malaria medications and get better. The following week or month, they may be bitten again. Again, they develop a fever and shaking chills. Again, they take malaria medications and get better. Eventually, though, after this happens a few times, they build up immunity. Even when bitten by infectious mosquitoes, they no longer develop symptoms.

If this person immigrates to a place where there are no more malaria-transmitting mosquitoes (like to the USA), their immunity gradually decreases, disappearing in 3-5 years. When they return to Africa to visit family members, they are likely to stay with their family and resume their old habits. They may not realize that they are no longer immune to malarial illness. When they are bitten by an infectious mosquito, they may become extremely ill and are at risk of dying.

Every year, around 5 people die of malaria in the United States. This is tragic. Although little in life is certain, travelers can almost 100 percent protect themselves from dying from malaria by taking prophylactic medication as prescribed by their doctors. Like most people, I do not love to take medication. But when I travel to a malaria endemic area, I always take prophylaxis. I know how quickly this disease can kill someone who is not immune, someone like me.

Back at Children’s National in Washington DC, things were progressing quickly. Once the malaria parasites were found in the boy’s blood, he was admitted to the intensive care unit. The doctors started him on an appropriate medication. Though everything was done correctly and promptly, the child deteriorated and lapsed into coma. He was diagnosed with cerebral malaria, the condition we study at the Blantyre Malaria Project in Malawi. Fortunately, 36 hours after he came into the hospital, he woke up. After 5 days he was discharged. No one else in his family became ill. I asked the pediatric intensive care unit doctors to be sure to educate his family about the need to take malaria prophylaxis in the future if they were going to travel to Nigeria or anywhere else malaria was endemic. The family had been in the USA for over 5 years. By now they had all likely lost immunity. Future trips would be hazardous unless they protected themselves. Now that they had the knowledge that they were newly at risk of dying from malaria, they needed to take action to stop themselves from joining the list of grim statistics, tragically dying from this preventable illness.